A Coalition of Science-Based Wildlife Professionals

STEPHEN NETT

FOR THE PRESS DEMOCRAT May 17, 2019

Sonoma County vintners using barn owls for pest control

High above the vineyard, Michael McGuire leans from his perch on a tall orchard ladder and signals: pay dirt. He’s peering cautiously into the dark interior of a rectangular wood box bolted to the top of a 15-foot metal pole amid rows of greening grapevines.

Usually, McGuire is out making house calls as an animal exclusion specialist for Sonoma County Wildlife Rescue. He’s the person people are happy to see when skunks go wild and spray under the house, or bats move into the attic.

Today he’s on a different mission. He extends his phone slowly into the box. From inside we hear a faint hissing shriek, like a broken steam pipe. After taking a quick video, McGuire retreats, then backs quietly down the ladder. In the video, we see three big fluffy white owl chicks. They all stare round eyed at the intruder. It’s mid-spring, and the three fledglings are what we came to find. It means barn owls have moved in and are nesting here, and that means the chicks’ parents are out on the job, keeping Quail Hill Vineyard from being overrun by hungry gophers.

Quail Hill’s 10 owl nesting boxes, staked out around the vineyard, are part of a small but rising trend among local growers. Supported by partners like Wildlife Rescue’s Barn Owl Management Project (BOMP), they’re enlisting wildlife to help on the farm.

Left to itself, nature is not particularly friendly to farmers. The standard approach to starting a vineyard is to clear away the natural vegetation and wild things, then use machinery and chemicals to fight off pests and keep out any competing plants.

But for the last decade or two, an increasing number of growers have been experimenting with a more organic approach, intentionally letting plants grow between the rows of grapes. The right cover crops, it turns out, can help manage water and improve soils. Equally important, they reintroduce a diversity of life to the vineyard, from healthy microorganisms in the soil, to insect-eating spiders.

Unfortunately, the verdant strips are also a lush green welcome mat for plant-munching rodents like gophers.

“Gophers and voles are particularly dangerous to grapevines,” says Jason Stalling, vineyard manager at Quail Hill in Sebastopol. “Gophers will chew through the base of a young vine in a single feeding session. Voles can girdle fully mature vines, if left unchecked”.

Rather than killing rodents with poison, the solution for Lynn and Anisya Fritz, Quail Hill’s owners, was to bring native wildlife back into the vineyard, as partners. That’s where the barn owls came in. By setting up specially designed nesting boxes, they hoped to encourage the raptors in the area to take up residence in the vineyard, raise a family, and in so doing, help manage the rodents.

As Wildlife Rescue McGuire’s ladder-top survey confirmed this April, it’s working. Quail Hill now contracts the Barn Owl Management Project to inspect, maintain and seasonally clean their owl boxes.

Around Sonoma County, a growing number of property owners are following suit. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of barn owl nesting boxes are now sitting on poles around the county.

Although barn owls are native to Sonoma County, few people ever see them, because they’re usually only out at night, and work in the dark. They’re a gloriously handsome bird, with soft rust and white mottled feathers, long silent wings, dark round eyes and a finely sculpted ruff around the face. Their main diet are the rodents that come out to graze after the sun sets.

To their prey, the first and last view of a barn owl is usually an oval basket of eight very sharp talons dropping silently from the night sky. The owls are remarkably good hunters, thanks to some impressive accessories, according to Dr. Matt Johnson, a Humboldt State University Wildlife scientist, who’s leading a first-ever study of their role in Wine Country vineyards.

They have amazing hearing, for example. “In studies,” Johnson says, “scientists found barn owls were able to locate and snatch prey in total darkness, relying just on sound.” It turns out, the characteristic mask around the owl’s face isn’t just for looks. “Those facial feathers actually channel and concentrate sound toward the owl’s ears, which are located at the edges of the ruff on either side.” The feathers work something like cupping hands behind our ears.

But do barn owls help Sonoma County vineyards and farmers? Surprisingly, no one had studied whether owl boxes were actually working. Johnson and his team are systematically studying them to find out.

“In the beginning I was skeptical,” he admits. “But when we did our surveys, we found that 25-50% of the owl boxes were occupied.”

After setting up infrared cameras, Johnson’s team began counting just how many rodents the owls were catching. “We found that a family with two adults and an average number of about four chicks was eating roughly 1,000 rodents per breeding season,” Johnson explains. That’s a lot of rodents, considering an owl pair can breed twice a year.

But why choose barn owls? They’re remarkably suited for the task, Johnson says. In the wild, they nest in cavities of trees and rocks. Much of their forest habitat has since been cut down. But beginning in the late 1800s, the people who cut down the trees also began raising wooden sheds and barns. The adaptable owls moved in – hence the name. They’re not particularly territorial, and evidently don’t have a problem living near human activity.

But, Johnson notes, they’re terrible at housekeeping. They’ll let their nests fill with pellets, waste and even dead birds. For that reason, owl boxes need to be properly maintained.

Vineyard owner Jim Rickards is more than happy to have barn owls nesting at his J. Rickards Winery, situated in the Alexander Valley near Cloverdale. He was one of the first pioneers to begin sowing cover crops between vines in Sonoma County, and started putting out owl boxes 30 years ago.

“Our vineyard was first planted in 1908. It was a horrid mess when I bought it. It had lost about a foot of topsoil over the years, because the gophers had burrowed so extensively, the hillside was washing out in rains,” he recalls.

He started planting crop cover between the vine rows in the late ’70’s — his own custom mix of grasses, clovers, mustard, even wildflowers. It was a radical approach at the time. “I stopped spraying in ’82, and everyone warned me, the vines would be eaten alive. But with the cover plants — sometimes you reap benefits you don’t expect. Instead, we found the bad bugs went away.”

The plantings encouraged gophers and insects, but also the wildlife that eat them. “In a rainy year there can be an exponential increase in mice, gophers and other vermin — but also in snakes and owls and other predators, if they’re given secure places to live in and around the vineyard,” Rickards says.

He now has eight owl boxes. “Last year’s survey found 17 chicks in six occupied boxes; with parents, that’s about 30 owls living on the property,” Rickards says.

Rickards partners with BOMP, and gladly pays them to maintain his owl boxes. It’s a much better use of his staff time and resources, he says, and the money goes to support the nonprofit Wildlife Center.

Doris Duncan is the executive director at the Sonoma Wildlife Rescue Center. She first got involved with the owl boxes following a near calamity and a chance meeting.

Among other services, the SWRC rescues and rehabilitates sick, injured and abandoned wild animals. On any given month, they’ll care for fawns, skunks and coyote pups, birds and bobcat kittens, as well as owls.

“Eight years ago, we lost our donated food source for our rescued raptors. Suddenly we were faced with having to buy $60,000 in rodents every year. About that time, we were in touch with Lynn Fritz at his vineyard. He said his ‘gopher guy’ was rounding up as many as he could catch, and we were welcome to them. We showed up at 7:30 one morning, and he had 90 lined up on the ground,” she says.

The Fritz’s asked Duncan if she would check their owl boxes. At the time, SWRC had an orphan barn owl chick at the Center, and Duncan got the idea to try and place it with a nesting pair in a box which already had chicks. They installed the chick, and when staff came back to check, they found it was thriving, and happily adopted.

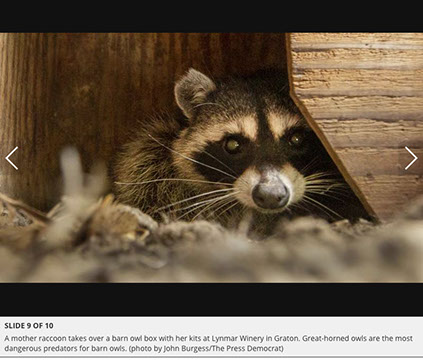

That started a hunt for additional adoptive barn owl boxes. Unfortunately, Duncan says, around the county, she found that many were in terrible condition or poorly designed. That was the genesis for the barn owl management project and its coalition of wildlife professionals and partners.

Today, a growing number of vineyards contract BOMP to install, survey and maintain their owl boxes, as well as the city of Cotati, a Petaluma school, ranches and residences. The fees paid for box maintenance go to support the rescue center’s rescue work and wildlife.

E&J Gallo Winery has been working with SCWR to help barn owls thrive for seven years, as part of Gallo’s Sustainable Rodent Control Program. “Owl boxes have been placed in a number of our coastal vineyards in partnership with SCWR and BOMP,” Robert Weinstock, director of Gallo Vineyard Operations notes, “and are maintained and monitored by SCWR. We look forward to our continued success in working together.”

From Matt Johnson’s perspective, these kinds of wildlife/agriculture partnerships are an important and promising trend worldwide. Environmental biologists know, he says, that its critical to conserve nature; but instead of protecting wildlife ‘from’ people, sometimes wildlife protection can also be ‘for’ people.

To Jim Rickards, the whole idea of sustainable farming — people ask him all the time — is that all the creatures have a share; he just wants to minimize them taking his share.

Doris Duncan puts it simply: she’s working for the day humans and wildlife can peacefully co-exist.

Stephen Nett is a Bodega Bay-based certified California naturalist, writer and speaker. Contact him at snett@californiasparks.com.

BOMP Coalition Administrative Office and Contact Information

Mailing Address:

Sonoma County Wildlife Rescue

PO Box 448

Cotati, CA 94931

Physical Address:

Sonoma County Wildlife Rescue

403 Mecham Road

Petaluma, CA 95452

Copyright Barn Owl Maintenance Program 2019 All Rights Reserved. - Hosted By Net10.net